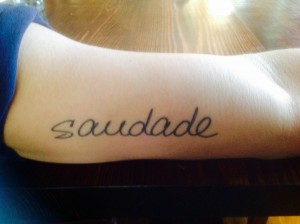

A reader whose younger sister recently died wrote me to ask how I endured, during the time of my daughter’s sickness and death, the silence of God. It’s something I’ve written about here and here, and in my book. I’ve talked about “saudade,” a Portuguese word meaning “the presence of absence,” which is how you feel, every day for the rest of your life, when you have lost someone you love. Their absence is a weight, it is a presence. You carry it with you everywhere. As I’ve written before, October—the month she died—still lays me low, so that I can barely function at times.

This weighty nothing is also what you feel when you cannot discern God’s response to your cries. It’s what you feel when you beg, when you bargain, and still death does not pass over your home, but comes inside, presses the breath from the lungs of the one you love, and then stays, a great shadow, a great nothing presence.

It feels like a betrayal, when God is silent. But what would I have him say? You are special, Tony. I’ll divert all the world’s suffering from your shoulders, because I love you more than the rest.

Yes, that’s exactly what I want him to say.

In truth it’s not the silence that crushed me, that enraged me, it was his refusal to give me what I wanted, which was to see my little girl grow up, to hear her voice like music in our house, to watch her married and to cradle her children, to go before her.

To go long before her.

He wouldn’t even give me what I begged for at the end, which was an easy death for her. Let the pain pass into me, sweet Christ, just ease her suffering.

Some of you know how I came unraveled in the years after, and what it cost the people around me. I told myself God was silent, and perhaps he was, though there were times, I realized later, when he spoke through small graces: a nap when she needed it most, the sweetness of an apple, her finger pointed to whatever she saw dancing about the ceiling, be it light or angels.

But maybe other times he really was silent, and maybe the reason is because I could not bear the answer.

Sometimes, after all, the answer is No. And when we ask why, the answer is little better: It is not for you to know. “May God give you grace…” said Israel to his sons as they took his youngest child into Egypt. “If I am bereaved, I am bereaved.” And Job, after hearing that all his children have died: “The Lord gave, and the Lord has taken away. As it seemed good to the Lord, so also it came to pass. Blessed be the name of the Lord.” Holy men looking heavenward to declare: Whatever I have was not mine, and so who am I to charge God with wrongdoing when he allows it to be taken?

This is a hard thing to hear, especially as you watch your beloved suffer. As you hear her try to draw breath, for in this she too is asking God, only to receive silence, and to join that silence with her own. The Lord gave her, yes, but how could he take her away?

How could you? I wept this at him. I spat it at him. How could you?

It is not for you to know. This is the truth behind much suffering. Far better people than me have written about what to make of this, and how to bear up under the burdens of this broken world, and I have no wisdom to add to theirs. I can only tell you what I think I have learned about the silence of God, which is, first, that I have often mistaken what I did not want—small mercies when a miracle is in order—for silence, and second, that sometimes silence is all we receive because we cannot yet bear the truth, which is that none of us is any more special than the other. We all of us labor in a sundered world and in it we are allotted our joys and our sufferings. Our deliverance often comes not, as Oswald Chambers noted, from these sufferings, but within them.

If nothing else, suffering lifts our eyes from this shattered plane to the world that is coming, that already dwells within our hearts, at least sometimes, and which will be written out in new flesh, in a new heaven and a new earth. We are sojourners through suffering and through mercies, not always in equal measure. But we are sojourners, which means this is not our home, yes, but which means also that we have a home to which we are going. We are stumbling homeward and we are battered but he carries us, make no mistake, even when he is quiet. Perhaps especially then.